Last week, Ohio Governor Ted Strickland vetoed the formation of a new Hemophilia Advisory Committee saying that one existed as a matter of Ohio law and had been dormant for years, and as such the new measure was redundant. In Georgia, Governor Roy Barnes delivered a veto this month to a measure that would have created a bleeding disorders advisory committee in the Peach State. Barnes argued that these advisory committees increase the size of state government. Instead, the Governor’s office will create a panel addressing bleeding disorders separate from legislative oversight.

In Massachusetts, its advisory committee continues to exist as a matter of law inside the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. While the committee exists in statute, it has never produced any usable data, or functioned in an official capacity. Though passed in the mid-1970’s six governors of both political parties have refused to fund the advisory committee. Meanwhile in Texas, the state’s Bleeding Disorders advisory committee was not re-authorized. The chapters in Texas are planning to self publish a version of the report its advisory committee had traditionally created for 2010 and 2011. Following Texas’ lead Connecticut lawmakers are convening a study committee to consider the needs of people across the state’s bleeding disorder community. Study committees are usually convened for a period of time where they address a particular issue, and produce a report. After the report is completed, the study committee disbands.

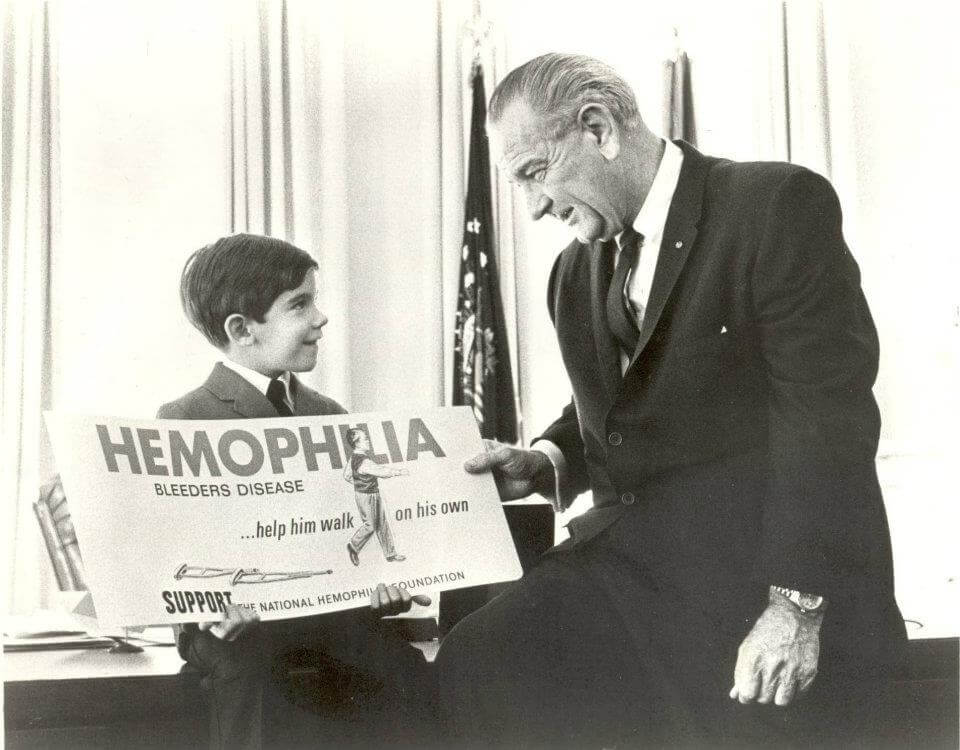

Advisory committees have been a centerpiece of state legislative action in the bleeding disorders community for many years now. The rationale for creating these panels was that having a place at the nexus of state government, administrative officials, and community members might better be able to access support and services from lawmakers and agency officials. The uneven experience of the various states begs the question: “is the formation of a committee the goal or the medium?”

Are the findings of fact that any advisory committee might create more important than the act of creating of the advisory committee? The findings inform political action, and that we can focus on. If we as a community can generate that list of needs with or without an “official committee, should we?”One could argue that credibility stems from our personal and professional experiences. Sharing our experiences creates an appropriate forum to address our community’s needs. The engine is much less important than the doing.

- Do we, as a community need, a formal process to generate the good ideas which could make our children, fathers, friends and families lives better?

- Is it possible that the leaders in our community are capable of generating the findings necessary to bring about real legislative, social and political action?

- Are there potentially, other ways to maximize the community’s impact in public policy with opinion leaders?

One might argue that having a single individual or entity on the status of care in our community is a public good, and that it is important to have some entity inside government accountable to the community, reporting on basic demographic information.