Hemophilia treatment centers have been around for almost 50 years. Learn about their history, successes, and new challenges.Â

By Rebecca A. Clay

At 58, Michael Birmingham, of Tacoma, Washington, is old enough to remember what life was like for kids with bleeding disorders before the advent of hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs). Diagnosed with severe hemophilia A at 13 months, he spent his early years going to the hospital whenever he needed infusions. Then he and younger brother, Pat, began getting care through a Stanford University pilot program that offered home infusion, which would become a hallmark of HTCs.

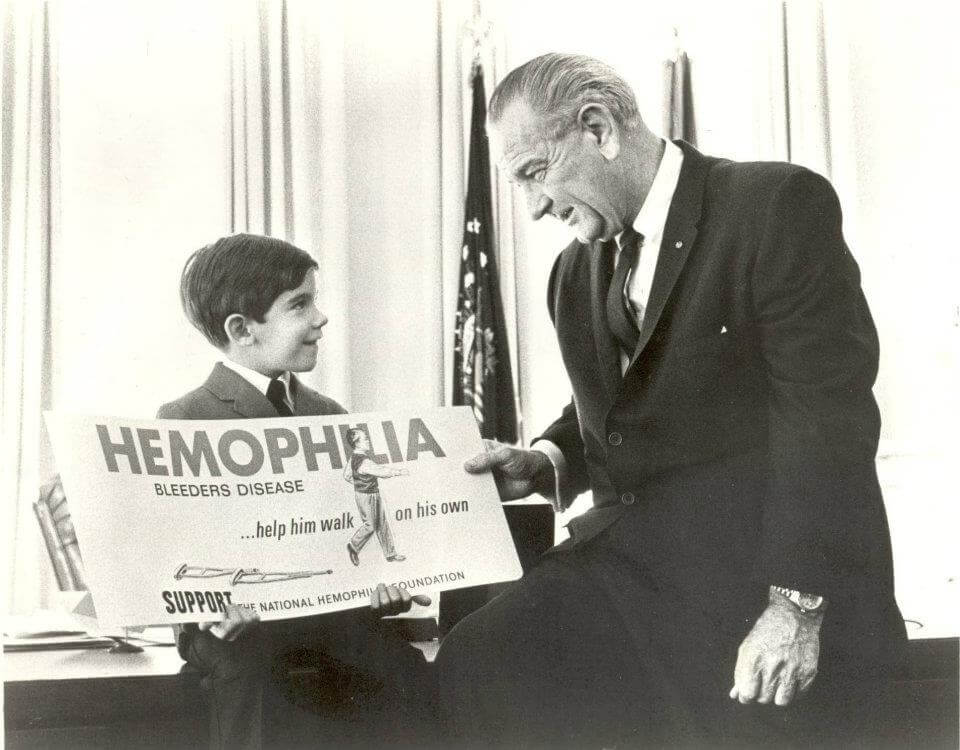

That care produced such great results that in 1973, when Birmingham was 10, his family traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify before a congressional subcommittee looking at legislation to create comprehensive hemophilia programs.

“Each of us boys had about a minute, and Dad talked for two or three minutes,” remembered Birmingham, who now works as a sales territory manager for a specialty pharmacy. The contrast between the Birmingham boys and others was striking. “The other kids brought in had obvious problems or talked about how hemophilia had caused limitations and problems,” Birmingham said. “We were just normal boys.” Although that bill didn’t pass, the boys’ testimony was an early step in the advocacy efforts that eventually led to the creation of today’s HTC system.Â

The first HTCs received federal funding in the mid-1970s, modeled after published examples of new interdisciplinary approaches to providing care to individuals with hemophilia,” according to a written statement provided to Dateline Federation by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), which helps fund the program through grants from its Maternal and Child Health Bureau. “Based on their success, HRSA started providing funding for organized regions of HTCs in the mid-1980s.”

Today, there are 149 HTCs across the United States, organized into eight regions. Their goal? To provide coordinated, team-based specialty care to meet the physical, psychosocial and emotional needs of people with hemophilia and

other rare inherited bleeding and clotting disorders.

What HTCs ProvideÂ

“You’ll hear this word ‘comprehensive’ care, and what that means is that you have full service,” said Zuiho Taniguchi, administrator of the HTC at Mount Sinai in New York and regional administrator for the New England region within the HTC network.Â

Patients typically come in annually for a full work-up by a core team comprised of a physician, nurse coordinator, social worker and physical therapist, with additional in-person, phone or video visits as needed. While the HTC itself focuses on specialty care, centers partner with clinicians and other providers to ensure patients get everything they need, whether it’s genetic counseling, access to a specialized pharmacy, or referrals to primary care physicians, orthopedists, dentists, gynecologists and other providers comfortable serving this patient population.Â

The care doesn’t just focus on physical issues, and it isn’t just for patients. “All kinds of parenting issues come up,” for example, said Judith Baker, DrPH, MHSA, public health director at the Center for Inherited Blood Disorders in Orange, California, and regional administrator for the Western States Region within the HTC network. “Some parents have tremendous guilt, thinking, ‘I gave this to my child,'” she said. “Siblings may feel ignored and act out.”Â

Educating patients, families and others in a patient’s orbit is another key function. Nurses teach parents of pediatric patients how to infuse their children and teach young patients how to infuse themselves. HTCs also work with local groups to get the word out about developments in the field, with staff giving talks on topics such as new products or insurance issues. HTC nurses and social workers even visit schools to ensure that staff are aware that a child has a bleeding disorder and know how to respond to their needs. HTC staff can also consult with other clinicians to ensure they know how to provide services safely, whether it’s a teenager having wisdom teeth removed or a person having a baby.Â

Long-term, trusting relationships are a hallmark of HTC care, said Taniguchi, who, as a 43-year-old with type 2 von Willebrand disease (VWD), is an HTC patient himself. “When I need something, I’m able to call my team,” he said. “They know me. That’s a big deal.”Â

Even if you don’t live close to an HTC, you can still get care, said Angela Blue, MBA, program director of the Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center at the University of Colorado’s School of Medicine in Aurora.Â

Local hemophilia groups often provide financial assistance-food, hotel rooms, even plane tickets-for patients who must travel for care. HTCs also travel to patients, bringing the entire team to provide services at outreach clinics. And while insurers are beginning to tighten up regulations that were loosened during the pandemic, telemedicine has proved to be a great way to expand access to patients with geographic or other barriers.

“I would encourage patients to ask for what they need; it would be unfortunate if a patient thought that some service wasn’t available where they were and so just didn’t bring it up,” Blue said. “If the HTC knows what their needs are, many times we can be creative in figuring something out.”Â

Patients also benefit from all the other activities that HTCs and the regional networks carry out, including research and the collection of data to monitor and better understand patients’ health and outcomes. Workforce development is also critical. Webinars, working groups and mentoring not only help HTC staff develop new skills but also overcome professional isolation.Â

Successes and Challenges

The kind of comprehensive, multidisciplinary care that HTCs provide pays off, according to researchers. Â

Research by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which uses HTC data to monitor the health of patients, has found that patients treated at an HTC are 40% less likely to die of hemophilia-related causes than those who received their care at other kinds of health care settings. Other research has found reductions in bleeding-related hospitalizations and the use of emergency room services, which means less absenteeism from school or work and lower health care costs. Plus, HTC patients like the care they receive, with 96% of respondents to a national patient satisfaction survey reporting that they were always or usually satisfied with their HTC.Â

But despite those successes, HTCs are facing challenges that could potentially threaten the existence of some centers, said Baker, who, along with local clinicians and hemophilia groups, helped establish HTCs in Nevada, Hawaii, Guam and California.Â

For one thing, the population of patients that HTCs serve is growing and evolving, making the care required more complex. Women with VWD comprise a large proportion of that patient population growth, which has led some HTCs to establish specialized women’s clinics to meet their unique needs.

The adult patient population is also growing-and aging. AIDS deaths of thousands of adults with hemophilia skewed the population toward pediatrics, which contributed to a scarcity of adult hematologists committed to hemophilia care, Baker said. One of today’s challenges is rebuilding the workforce to ensure sufficient numbers of providers for adults as well as children. Â

While the complexity of care is increasing, funding is not. One issue is the erosion of support from hospitals, which house most HTCs. In the 1990s, Baker said, hospitals began shifting toward a for-profit model, with specialized, prevention-oriented, team-based inpatient care for rare disorders increasingly viewed as unprofitable.Â

Another problem is the way reimbursement is structured. “Reimbursement favors inpatient stays, what’s called ‘heads in beds,’ and procedures like chemotherapy infusions and other things that can be done in hospitals,” Baker said. In contrast, many key HTC services-care coordination and telephone consultations, for example-are often poorly reimbursed or not billable at all.Â

Meanwhile, federal funding hasn’t kept pace with increased needs. “Congress has not increased funding for our grants from HRSA or the CDC for many years,” Baker said. The HRSA Regional Hemophilia Network grant, which supports comprehensive bleeding and clotting disorder care, doesn’t cover the cost of a full-time nurse, she pointed out, while the CDC grant, which supports surveillance to monitor health outcomes, barely covers the cost of a full-time data manager or clinical research associate.Â

To help make up the shortfall, most HTCs participate in the federal 340B drug pricing program, which allows HTCs and other entities to purchase outpatient drugs at discounted prices, sell them to patients and use the margin to help support care.

“Per Congress, all pharmacies that use 340B prices must reinvest program income to stretch scarce federal resources to provide more services and reach more patients,” Baker said. But even that income stream is threatened, she added. Some state Medicaid agencies and other insurers set reimbursement rates for outpatient drugs at sub-optimal levels, and newer drugs that require fewer doses can mean less revenue when the reimbursement model is solely based per prescription. Â

Patients and families can help ensure that HTCs can survive and thrive, she said. “Connect with Hemophilia Federation of America and National Hemophilia Foundation chapters and work within a team of advocates to make your voice heard,” she suggested. “You can tell your story as part of a unified message to ensure that everyone has access to an HTC who needs one.”