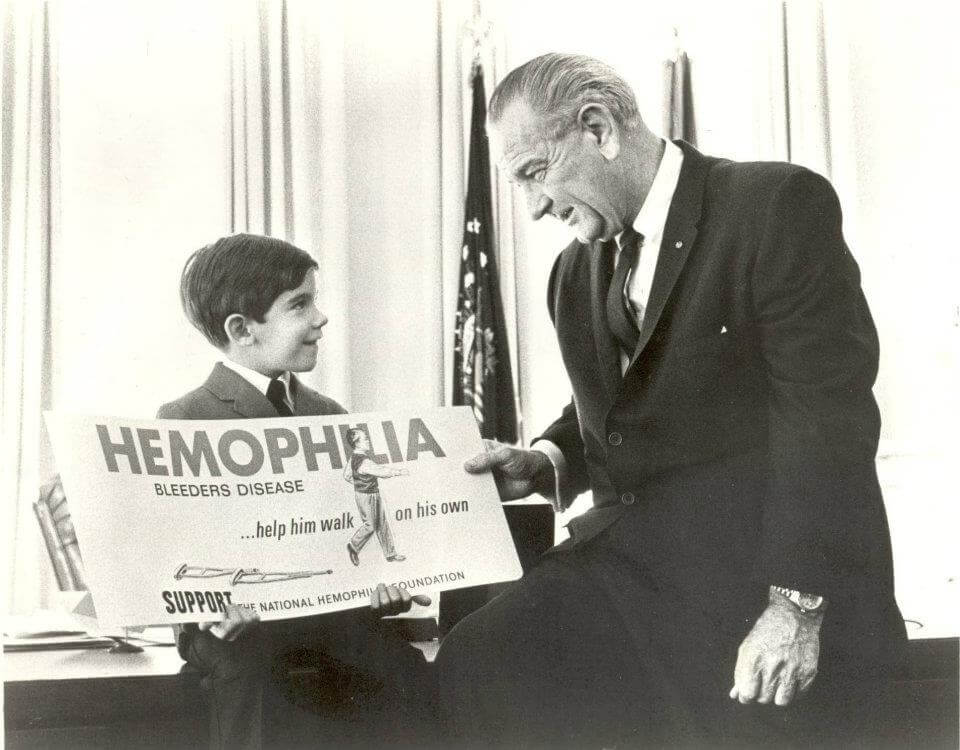

By HFA Policy and Advocacy Team, with assistance from an actuarial professional.

For many in the bleeding disorders community, drug manufacturer copay assistance programs are a source of financial relief and the sole protection against perpetually high out-of-pocket health care costs. Unfortunately, health insurers, citing the need to curb medical inflation, are increasingly refusing to credit copay assistance toward patients’ deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums, via the implementation of “accumulator adjuster programs.”

This strategy shifts thousands of dollars of cost-sharing back to the patient. Because the implications of this shift are far-reaching, addressing this issue has become a top advocacy priority for HFA and many other patient advocates.

Accumulators create significant confusion, financial risk and barriers to care. Those confronting high-cost sharing may find themselves hard-pressed to afford their prescription refills, forcing them to weigh discontinuing treatment or turning to emergency rooms for care. Both options lead to bad health outcomes and higher overall health spending in the near term. But people exposed to high year-after-year out-of-pocket costs also face long-term, grossly disproportionate threats to their financial security as well as their physical well-being.

When copay assistance is working as intended, it greatly reduces the cost-share for those who must rely on ultra-high-cost drugs. It effectively levels the playing field, bringing out-of-pocket expenditures for this population down to a level that is comparable to a person of more typical risk. Should accumulator adjusters be allowed to spread across the insurance landscape, copay assistance would no longer be an effective tool to combat high patient cost-sharing. Suddenly, many with a bleeding disorder could face the maximum out-of-pocket costs allowed under their health plan, year after year after year. The level playing field would be gone and those who rely on high-cost drugs to preserve their health would face a financial burden starkly different from those of more typical risk.

There is evidence proving this is already happening: A 2019 article from RealClearHealth.com reported, “On average, individuals with two or more chronic diseases spend five times more out-of-pocket than patients without any chronic conditions. People with three or more conditions pay 10 times more.”

To illustrate, examine the out-of-pocket claims spend of two individuals: Maximum Mike and Average Joe. Both have an Affordable Care Act Marketplace plan with an out-of-pocket maximum of $8,550, the upper limit allowed for 2021. Maximum Mike has a chronic condition requiring expensive medication, so he will reliably reach his plan’s OOP limit each and every year. Average Joe spends the U.S. average on out-of-pocket costs, which is $800 per year, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The table below shows their cumulative spending over time. (For this exercise, both the ACA out-of-pocket limit and U.S. average out-of-pocket spend are assumed to increase 4.4 percent each year. This matches the average annual increase in the ACA out-of-pocket limit from 2014 to 2021.)

In year one, Maximum Mike tops out his out-of-pocket spending at $8,550 – compared to Joe’s out-of-pocket cost of $800, for a difference of $7,750. With no protection from copay assistance, this dynamic plays out year after year and Mike quickly faces an overwhelming cost burden. Within 10 years, his costs exceed $100,000, while Joe’s remain under $10,000. The following graph highlights this huge cost disparity.

In summary, it is clear that accumulators cause serious short-term and long-term harm to individuals who rely on high-cost drugs to maintain their health. Maximum Mike and Average Joe are imagined, but the comparison of their projected spending over time is not merely a theoretical exercise. These charts show hard-earned money not being put in a 401k, not being saved for college, not being spent in pursuit of the American dream. They show lost opportunities that will become reality for our families and friends if accumulator adjusters continue to proliferate. As a community, we must understand the threat that accumulator adjusters pose, educate our lawmakers and advocate for change.

Terms to Know

The insurance landscape includes language that can be confusing. These common terms are important to know:

Accumulator Adjuster Program: Accumulator adjuster programs are strategies that pharmacy benefit managers implement, often, but not only, in connection with large group employer health plans. AAPs apply to patients who use drug copay cards and other forms of manufacturer copay assistance. Under an AAP, a pharmacy benefit manager accepts copay assistance for out-of-pocket costs associated with a prescribed drug, but then doesn’t credit that amount toward the patient’s overall deductible or out-of-pocket maximum. This means that the PBM will draw down the full value of the copay card and still require the patient to pay copays (for additional medication fills, doctor’s visits, etc.) up to the yearly out-of-pocket maximum. The manufacturer assistance will not apply toward satisfying the yearly maximum.

Affordable Care Act: The ACA is a comprehensive health care reform law enacted in March 2010. Often referred to as “Obamacare,” the ACA’s reforms affect nearly every American in some way. The law creates paths to coverage for people who do not get insurance through their jobs; protects the ability of people with preexisting conditions to obtain insurance on a non-discriminatory basis; requires Marketplace plans to cover essential health benefits, including prescription drugs; eliminates lifetime and annual caps on health benefits; limits yearly out-of-pocket exposure for patients; and more.

Claim: A request for payment that you or your health care provider submits to your health insurer after you receive covered items or services.*

Coinsurance: Your share of the costs of a covered health care service, calculated as a percentage (for example, 20 percent) of the allowed amount for the service. You pay coinsurance plus any deductibles you owe. For example, if the health insurance or plan’s allowed amount for an office visit is $100 and you’ve met your deductible, your coinsurance payment of 20 percent would be $20. The health insurance or plan pays the rest of the allowed amount.**

Copayment: A fixed amount (for example, $15) you pay for a covered health care service, usually when you get the service. The amount can vary by the type of covered health care service.**

Copay Assistance: Copay assistance (sometimes called “copay cards” or “coupons”) is money that helps patients afford out-of-pocket costs for their medications. Patients with chronic conditions such as bleeding disorders need specialty medications to manage their disease. Copay assistance is often the only way that they can afford the out-of-pocket costs for their life-saving medications.

Cost Sharing: The share of costs covered by your insurance that you pay out of your own pocket. This term generally includes deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments, or similar charges, but it doesn’t include premiums, balance billing amounts for non-network providers or the cost of non-covered services.**

Deductible: The amount you owe for health care services covered by your health insurance or plan before your health insurance or plan begins to pay. For example, if your deductible is $1,000, your plan won’t pay anything until you’ve met your $1,000 deductible for covered health care services subject to the deductible. The deductible may not apply to all services.**

Out-of-Pocket Limit: The maximum amount you will be required to pay for covered services in a year before the plan covers 100 percent of all costs. Generally, this includes the deductible, coinsurance and copayments (varies from plan to plan), but not premiums. Plans can set different out-of-pocket limits for different services, and some plans do not have out-of-pocket limits.*

Premium: A monthly or annual payment you make to your insurer to get and keep insurance coverage. Premiums can be paid by employers, unions, employees or individuals or shared among different payers.*

* Resource: National Hemophilia Foundation Glossary

of Commonly Used Health Care Terms

** Resource: Healthcare.gov Glossary